What does it truly mean to preserve history? Not just the preservation of knowledge, but the preservation of history, the hand-written texts that are scrawled across vellum manuscripts that pre-date our own American history by centuries?

This type of preservation is exactly the sort of work University of Utah Preservation Librarian Randy Silverman engages in on a regular basis, and was the focus of his most recent work in Uzbekistan through the Fulbright Specialist Program.

Silverman first visited Uzbekistan in November 2013 through the U.S. Embassy, where he worked with the National Library of Uzbekistan’s staff through a series of lectures and workshops. During his trip he was introduced to the idea of returning to Uzbekistan to aid in preservation through the U.S. Embassy who suggested the project would be an ideal fit for the Fulbright Specialist program.

As part of his Fulbright work Silverman was given the opportunity to travel to work with the National Library in Uzbekistan twice in early 2015.

During his time in Uzbekistan, Silverman worked with the National Library there to teach good preservation techniques, and to help establish a base line for quality preservation for distribution to libraries across the country.

The resulting publication titled “Preservation Considerations for Uzbekistan Libraries” is now being translated into Uzbek with the National Library.

According to Silverman, the importance of this type of work simply cannot be understated. The historical value of collections such as the one housed by the National Library are significant.

“A country like Uzbekistan has a cultural heritage that is astounding,” Silverman said. “During the Medieval period Uzbekistan was a world leader in science, astronomy, math, and even existed on the Silk Road [trading route] coming out of China and going into India and Europe. So they dealt with not only the movement of goods, but also the movement of ideas, putting them at the height of intellectual achievement at the time.”

Silverman explained that due to its rich history, Uzbekistan houses some of the most significant manuscripts on Islamic history in the entire region stretching all the way to Saudi Arabia.

During the trip, Silverman lectured at the annual International Library Conference for Central Asia, marking his third time speaking at the gathering. He also put on workshops at two of the regional libraries in the country as well as lecturing at three of the local universities during his time there.

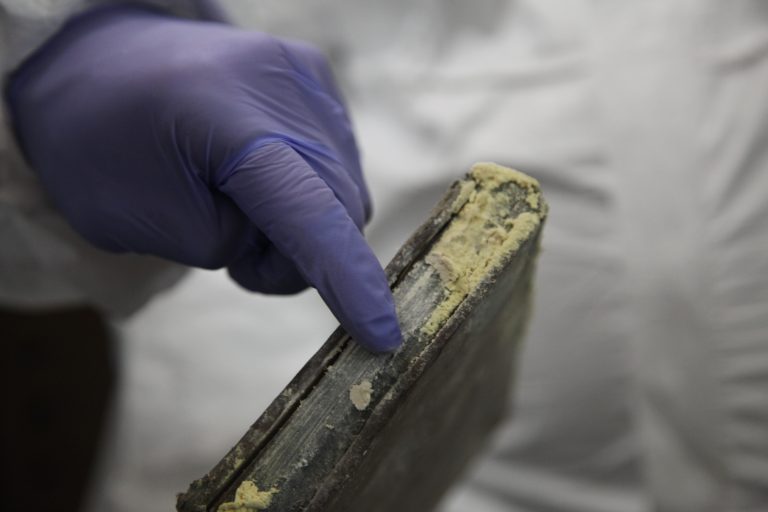

“I worked with their primary conservation staff to show him some conservation techniques, and took the tools and materials for that with me, because they didn’t have any,” Silverman said. “I also worked with the library staff on environmental monitoring using little monitors I brought with me.”

According to Silverman, the library had already been monitoring temperature and humidity both inside and outside of their rare book vault, but was unsure what to do with the raw data. During his time there, Silverman helped them chart the data so they could better understand the way the weather outside the vault was affecting the environment inside, and the potential adverse effects the weather could be having on their collection.

In reality, the necessary action to keep prized collections intact is really quite simple, Silverman explained. Little things such as keeping the books in a cool, dry, dark place is enough to double or even triple the life of these collections.

This sort of preventative preservation is done through basic means such as storing books and manuscripts in individual boxes, within rooms that are kept well insulated and cooled. These are the same techniques employed by the conservation lab here at the University of Utah.

“It is very exciting work, because by doing very little, we are able to extend the survival of these world treasures in a huge way,” Silverman said. “My goal has been to establish conservation standards in a country that is ripe to adopt those standards. I’m very hopeful that my visits will influence the way that people think about controlling the environment for their collections.”

As for the future of preservation work in Uzbekistan, Silverman was very excited to have made some headway with the National Archive of Uzbekistan. Unlike the National Library, the National Archive is a much more restricted collection of historically significant items that are generally off limits to most people within the country, and even more so to foreigners.

“For me, this is a huge step forward because usually the archives are completely out of bounds to even the local Uzbeks, much less an outsider, but they are facing the same preservation problems, and I believe I can do some good there as well, so I hope that continues to move forward.”

Silverman’s work through the Fulbright program has been approved for the next five years. Having completed one project in Uzbekistan, he must wait an additional two years to pursue another project, but remains hopeful that he will be able to do so.

Additionally, Silverman is in the planning stages to bring the conservator from the Oriental Institute in Uzbekistan directly to the University of Utah within the next year.

“This would be a huge step forward, because for them to see a lab like ours, the tools we use, our layout and use of light and water, the materials we use and why we use them, would move their conservation forward in a dramatic way,” Silverman said. “The National Library has been telling me they want to build a conservation lab since I first visited, and it’s my hope that I can further the advance of this bridge into Uzbekistani conservation by bringing someone here.”